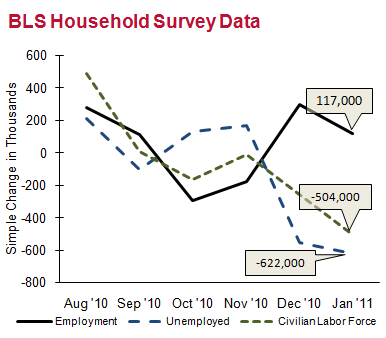

In the figure above, the simple change in the civilian labor force (the number of able-bodied adults not in the military), employment (the number of people in the civilian labor force with a job), and unemployment (the number of people in the civilian labor force without a job) are plotted. We are encouraged to see that there were 622,000 fewer unemployed persons in January, but that encouragement is short lived when we realize that only 117,000 of those people found jobs. The rest left the labor force, in other words, stopped looking for a job. Thus, this is one of those times when a lower unemployment rate is not a good sign. In fact many economists, myself included, expect the unemployment rate to increase as the labor market begins to recover in earnest because formerly discouraged workers will reenter the job market.

So how may jobs were added to the economy last month? 36,000 or 117,000? That depends on who you ask. The two numbers come from two surveys conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics: a survey of households and a survey of businesses. The survey of businesses may not be counting all of the new jobs in the economy because very new businesses are not included in the survey. Why? Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics do not know they exist yet or how to contact them. Whichever number we accept, the conclusion is the same: the economy is not creating jobs fast enough to make a significant dent in unemployment. This is not unexpected, though.

Recessions like the last recession are rare and particularly nasty. The last recession was caused by a financial market collapse not unlike what sparked the Great Depression. A careful examination of recessions of this type throughout history reveals that one common feature is a particularly long and slow recovery period. The unfortunate truth is that there may be no macroeconomic policy we can take that will be effective in lowering the unemployment rate in the near future.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.